Hello, everyone, and welcome back to Bio On The Rocks. After giving you a detailed summary of the “Arctic Environmental Management” course, which has now concluded, I thought it would be an excellent opportunity to discuss upcoming projects. My other course, which is now running parallel and becoming very intensive, is “Arctic Marine Biology.” In this course, we have looked at the different trophic levels of the marine food web in the Arctic, including the dangers and changes they face, as well as the changes in species composition in recent years. Last Wednesday, we had our final lecture unit with a lab component that dealt extensively with zooplankton.

In line with this, I have already given you a deeper insight into the base of the marine food web and discussed the pressure that ice algae, as well as phyto- and zooplankton, are under due to the loss of sea ice. If you missed it, read my post, “Let’s dive deeper.”

Now is the time to put what we’ve learned into practice and test our species knowledge on fresh samples. Therefore, we – that is, my eighteen classmates, a few lecturers, an experienced crew, and I – are setting off on Wednesday aboard the ship “Helmer Hanssen”. The Helmer Hanssen, a Norwegian research vessel of the University of Tromsø, is primarily used for oceanographic, fisheries, and climate research. In particular, the University of Tromsø, the Institute of Marine Research in Bergen, and, of course, UNIS use this ship for their research.

We will spend four nights and five days on the ship, taking samples of phytoplankton and ice algae, zooplankton, benthos (organisms at the sea bottom), and fish at various locations west of Spitsbergen. We will identify these samples and contextualise them with data we already have from previous years. From this, we hope to be able to interpret the changes that have occurred and discuss, for example, where a possibly reduced diversity of phytoplankton comes from. But I will definitely report back to you in detail about this after the cruise, as well as what life on the ship was like.

One thing I can say right now is that it is a great honour and a huge opportunity to participate in this cruise. I have always enjoyed being on ships. At the age of five, I went on my first whale-watching tour near the Lofoten Islands, and I’ve always found the feeling of being exposed to the elements on a ship fantastic. This has not changed over the years, and fortunately, I have never developed seasickness. Let’s hope that remains the case next week.

However, for another reason, it is also incredibly special for me to be able to be on the Helmer Hanssen. This is the same ship Prof Matthias Forwick from the University of Tromsø and Dr Seung-Il Nam from the Korean Polar Research Institute used in 2017 for an expedition in the waters off Svalbard, during which they took several sediment cores. But what does this have to do with me?

Perhaps I haven’t told you in detail here yet. Quite early in my BioGeo studies in Jena, I had the opportunity to work in the palaeontology group of Prof Peter Frenzel. Among other things, I helped a doctoral student select her sediment samples for ostracods. This was my first contact with microfossils.

Microfossils, like other fossils, are remnants of organisms. They can be entire organisms, seeds, or even the shells of tiny organisms, often composed of calcareous material. As the name suggests, these are very small fossils, less than 3mm in size, and often not visible without a microscope. One might think that they do not play as significant a role in science compared to large fossils like the infamous bones of dinosaurs or, more recently, mammoth tusks. However, the opposite is true. They play an increasingly vital role in reconstructing past climates, allowing us to make more realistic projections for the future.

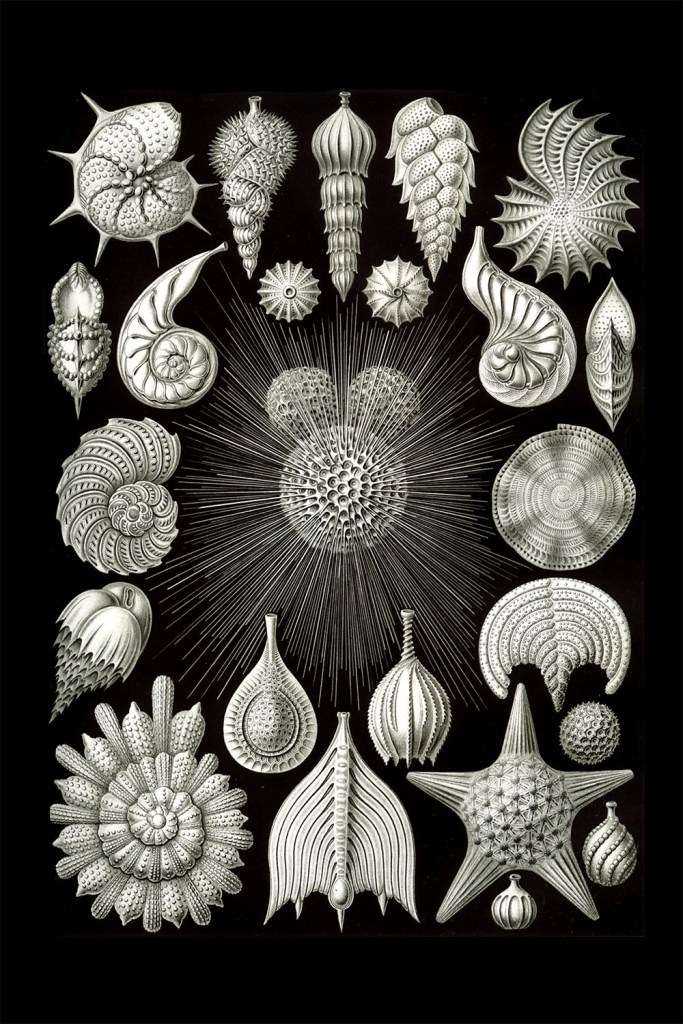

I would like to briefly introduce you to two types of microfossils that are particularly relevant to me. One of the most well-known groups of microfossils are the foraminifera. Foraminifera have been proven to inhabit the oceans since at least the Cambrian period, which means well over 500 million years. These are single-celled organisms, which is even more impressive when considering the incredible diversity of their calcareous shells, from simple tubes to very complex structures. There are forms with a single chamber to those with chambers in the double digits. Over 40,000 fossil species are known, and about 10,000 extant species still live today, of which, however, only 50 species occur in freshwater.

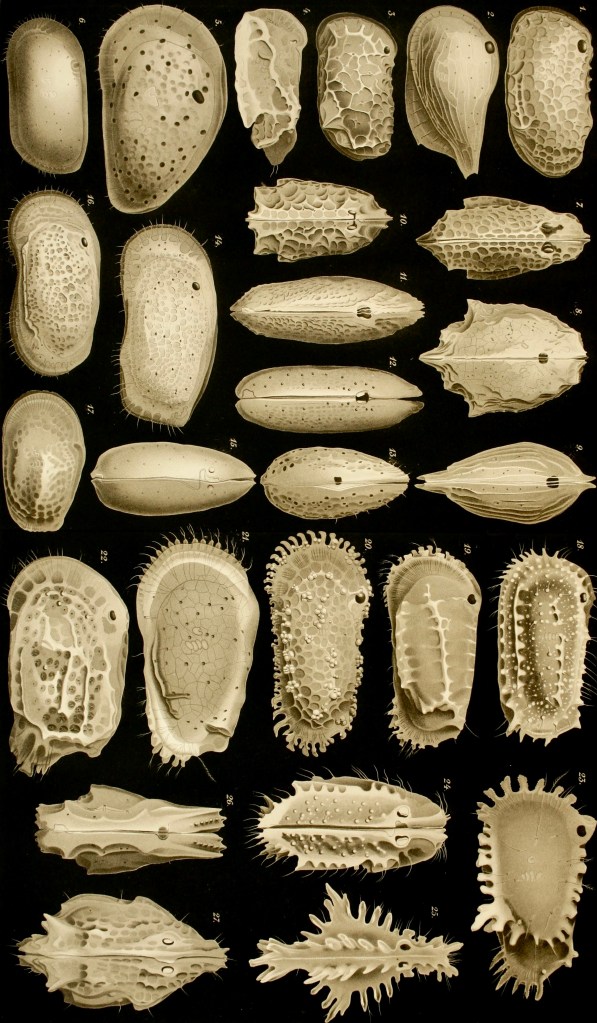

Another group is the ostracods, which my professor of palaeontology specialises in. Prof Frenzel has built a scientific circle around himself, focusing on them. Ostracods, also known as seed shrimps, are a fascinating group of microscopically small crustaceans with remarkable diversity and a long geological history. These tiny organisms can be found in almost all aquatic habitats, from deep oceans to fresh and brackish waters and rivers. Their characteristic feature is their two-part, shell-like exoskeleton, which looks like miniature bivalve shells and gives them their name. These shells are made of organic material containing calcite and protect the ostracod’s soft body.

Foraminifera and ostracods are sensitive to their environment, and changes in temperature, salinity, and other environmental conditions can be recorded in their shells. However, their fossil shells in sediment cores are often well-preserved and serve as archives for us. The scientific significance of microfossils thus lies in the ability to draw conclusions about the historical conditions of the oceans and terrestrial waters, which is crucial for understanding the Earth’s climate system.

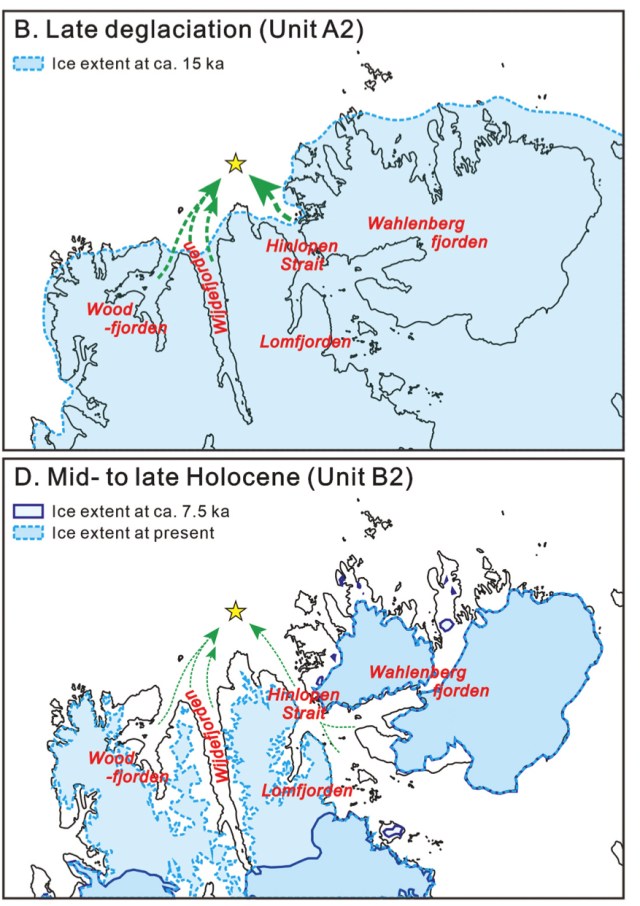

Having been interested in the cold regions of our planet for years, it has long been a captivating thought for me to possibly contribute to climate reconstruction in Arctic areas someday. Through my position as a scientific assistant and contact with the palaeontology working group, I’ve also developed a great interest in microfossils as climate indicators. Therefore, it quickly became clear that I wanted to write my bachelor’s thesis in this field. Since we currently do not have sediment samples from Arctic regions available at our institute for a BA thesis, I started looking for suitable material myself. Through several intermediaries and the support of the BDG (Professional Association of German Geoscientists) team, I managed to get in touch with Prof Forwick in Tromsø. He was very helpful and eager to assist me in finding the material. Together with his friend and colleague, Dr Nam, we discussed how to proceed. Now, I have the great fortune to work on one of the sediment cores, which the two working groups collected in 2017 during the sampling in the north of Svalbard.

At the end of April, I will leave the small town of Longyearbyen for a few days to fly down to Tromsø. There, I will work on the core and take sediment samples. After completing my semester in Svalbard in mid-June, I can start examining my samples for ostracods and foraminifera in Jena. I will be looking at time periods that are over 15,000 years old. Not only will I determine the species composition of the fossils, but I will also conduct a chemical analysis of the fossil shells as part of an internship at the Alfred-Wegener-Institut. Through this, I hope to be able to make numerous statements about the paleoenvironmental conditions in the Arctic Ocean north of the Hinlopen Strait.

So, spending the coming week on the ship Helmer Hanssen in the Arctic Ocean at a place I’ve wanted to be for years and being able to combine my passions for the polar regions, the life sciences, and the geosciences means a great deal to me. I am incredibly eager to see how this Bio On The Rocks moment will turn out for me, and I look forward to reporting back to you soon.

Right: The monument of the actual Helmer Hanssen, who became known for his services as a musher and advisor to Roald Amundsen on the South Pole expedition. (Check out the BlogPost “The sled dog Balto and his friends”) It is located in the city of Tromsø, right in front of the polar centre. Tromsø is known as the gateway to the Arctic. Phil Masters, 08.04.2024.

Relevant Paper for my thesis:

Kwangchul Jang, Youngkyu Ahn, Young Jin Joe, Carmen A. Braun, Young Ji Joo, Jung-Hyun Kim, Germain Bayon, Matthias Forwick, Christoph Vogt, Seung-Il Nam. Glacial and environmental changes in northern Svalbard over the last 16.3 ka inferred from neodymium isotopes. Global and Planetary Change, Volume 201, 2021, 103483, ISSN 0921-8181.