Hello, everyone, and welcome back to Bio On The Rocks. Even for me, it almost feels like a “welcome back” since I haven’t posted any new articles in the last two weeks. One main reason for this was that I had a visitor. My husband braved the long journey here, and we were able to spend ten days together in Svalbard, exploring the area. Among other things, we visited an ice cave (a different one from the one I reported on a few weeks ago), saw the Adventfjorden and Isfjorden from the waterside, went hiking, visited a museum, etc. We really enjoyed the time and gathered countless impressions, both in photos and on video. That alone would definitely be enough to write four posts. But actually, something else happened before Rick arrived, which I wanted to talk about first.

Two weeks ago, on Thursday, along with two others from my course, I gave our presentation on sled dogs in Svalbard and their environmental impact, which I had already announced in the last post. This was one of the two main tasks in the “Arctic Environmental Management” course. The following Monday, I had my oral exam in this subject and thus completed the course. This offers an excellent opportunity to tell you more about what we learned in this course.

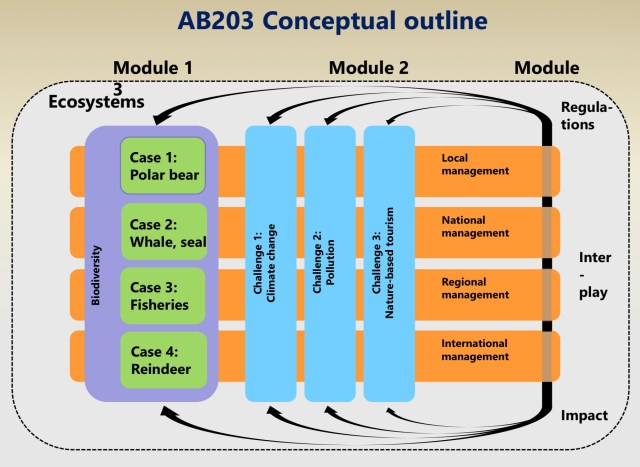

First off, what is environmental management? “Environmental management” refers to the systematic approach to developing, implementing, and monitoring policies and measures aimed at protecting the natural environment and using it sustainably. In our case, the focus was on Arctic nature, paying special attention to polar bears, reindeer, fish, and marine mammals like whales and seals. These organisms are in a particularly sensitive and vulnerable state in the Arctic, each living in an equally delicate ecosystem. Interestingly, the terrestrial and marine ecosystems are also interconnecting a lot.

We examined the various aspects that negatively or changeably impact populations and what measures can be taken at a political level to minimise the adverse effects on species. This involved examining regulations and concepts at local, regional, national, and international levels.

In short, management involves the following steps:

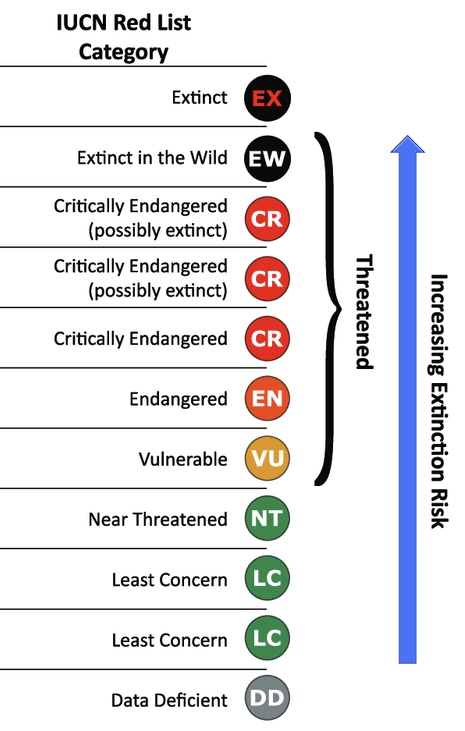

First, it’s necessary to determine how many individuals or what population size of a species is desired. Each country sets this for itself. However, there are guidelines that many nations follow for a healthy population size, such as the IUCN Red List.

The IUCN Red List (International Union for Conservation of Nature) is a comprehensive directory assessing the global conservation status of animal and plant species. It classifies species according to their risk of extinction, from “least concern” to “extinct,” to highlight the need for protective measures and promote the conservation of biological diversity worldwide.

To find out the size of the population I want to care for, various approaches significantly differ from one animal to another, depending on the biology of each organism. In some areas like Svalbard or the Barents Sea, helicopter flights and other aerial surveillance methods are used to count polar bears and seals and observe their behaviour. These methods allow researchers to efficiently monitor large, inaccessible areas without disturbing the animals. Besides helicopter flights, satellite images, drones, and other remote sensing technologies can also be used to gather information on the population sizes and distribution of animals. However, it’s important to note that counting animals in these remote areas is challenging, and the estimated numbers can be subject to significant uncertainties.

Over time, methods for tracking wildlife populations, including those of polar bears and seals, have significantly improved. Earlier estimates often relied on limited observations made through direct sightings or indirect signs like tracks in the snow. These methods could be inaccurate, especially in hard-to-reach or vast areas.

With the introduction of recent technologies, data can now be collected with higher precision and over larger areas. However, improvements in data collection could lead to an apparent increase in population sizes that doesn’t necessarily reflect an actual increase but rather a more accurate capture. Therefore, it’s essential to consider the data collection methods when evaluating population data over time. Long-term studies and historical data must be carefully compared with current survey methods to identify actual trends in population dynamics.

Once I’ve determined a population size with most uncertainties removed, I must decide: Is the number of desired animals in my region, country, or area around the same as I want it to be? Are there too few organisms, or perhaps even too many?

From there, I can now explore the particular threats the population faces and what might be the fundamental causes of a population decline. We took a closer look at the usual suspects: climate change, pollution related to chemicals and plastics, and the impact of intensive tourism. At first, these factors might have some very obvious negative effects on various Arctic organisms, but often, it’s the details that are crucial for population development. The question often is how adaptable the individual species are to the changing environment. And the answer to that varies greatly. I want to touch on a few examples here.

Reindeer in Svalbard face several difficult situations. Due to the warmer climate, increasingly warm temperatures during winter lead to above-freezing temperatures and “rain-on-snow” events, creating thick layers of ice that make moss and lichens inaccessible to many reindeer. However, reindeer are now also seen more frequently eating seaweed along the coast or climbing high into the mountains where it’s too steep for dense snow and ice layers. However, this exposes them to new dangers, such as getting entangled in stranded fishing nets on the coast. On the other hand, they are now also facing a higher threat from polar bears, as these have started to hunt reindeer in recent years, in addition to the less commonly found seals and whale carcasses. On a positive note for the reindeer, the later onset and earlier end of winter, resulting in a longer vegetation period, seem beneficial.

Another example is the wide world of seabirds. I could spend hours reading, talking, and philosophising about this topic. As the name suggests, seabirds find their food in the sea and depend on what they can find there. Some seabirds strictly specialise in one type of fish, like the Brünnichs Guillemot, for example. However, due to warmer conditions leading to significant changes in fish diversity in the Arctic, these highly specialised birds now have a harder time finding their preferred food. Therefore, it’s not surprising that plastic parts are increasingly found in the stomachs of many birds, mistaking them for food. Opportunistic birds, on the other hand, manage pretty well and are content with the prey they can find. Some seabirds that nest on the ground are now more frequently disturbed by arctic foxes and polar bears, which eat their eggs or chicks. Meanwhile, other seabirds benefit because the northward spread of fish and milder temperatures make new breeding regions possible.

I want to clarify here that there are always losers and winners in these tangled and complex systems, and it’s not easy to estimate which factors might have the biggest effect on a population. Some problems can be tackled quite well at a local and regional level. For example, the impact of tourism on nature and the ecosystem of Svalbard is already limited in some areas by the regulations set by the “Svalbard Environmental Protection Act”. Here, you can find regions that may not be entered or only with permission, year-round or seasonally, where ships may dock, how close one may approach polar bears, and several other regulations. In fact, we are currently awaiting the next “White Paper”, expected to be published this spring, with new stricter regulations, especially for tourism here in Svalbard, to protect nature and organisms.

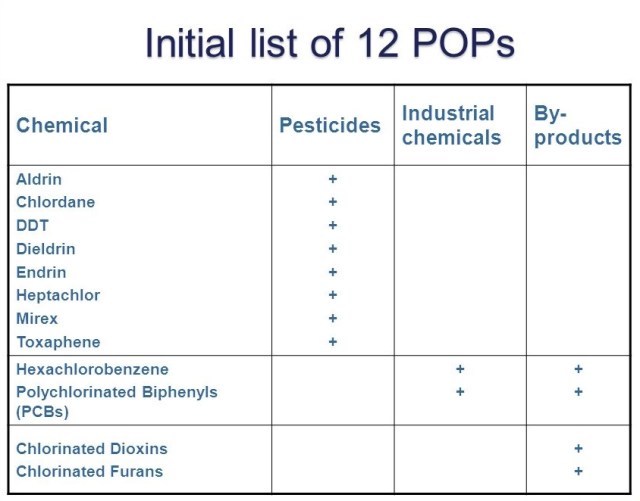

Other issues, like pollution and climate change, are so large and global that regional changes are just a drop in the ocean. Yet, the Arctic suffers the most from these problems, as it warms three times faster than other regions of the world. Also, vast amounts of chemicals and plastic waste find their way to the Arctic via wind and ocean currents. To tackle these problems, international agreements have been made.

For example, the Stockholm Convention is an international agreement focused on protecting health and the environment from persistent organic pollutants (POPs). These long-lasting chemicals accumulate in living organisms and can have harmful effects. Signed in 2001 and effective since 2004, the convention aims to eliminate or significantly reduce the production, use, and release of POPs.

Or the perhaps more well-known Paris Agreement, a global accord under the United Nations that aims to limit climate change and its impacts. Agreed upon in 2015, it commits participating countries to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions to keep global warming well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, aiming to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees.

Some countries are doing well in meeting their targets for this agreement, but of course, this opens a new debate and a broad field I won’t delve into right now. Maybe another time.

To say a few final words about this course: The subject is complex, even more complex than it might seem here, and certainly more complex than I initially thought. Admittedly, I struggle with laws and political topics. The fine precision and the small details often hidden in a few words of legislative texts remain a puzzle to me. However, I have found once again that I thoroughly enjoy interdisciplinary subjects. The various interactions in ecosystems between biology, hydrology, geology, and chemistry have fascinated me anew. And I think there’s a lot of potential to write more about this in the future on Bio On The Rocks.

Image 1: The sea ice loss in the Arctic over 20 years averaged 10,000 tons per second. This corresponds to four Olympia Swimming pools of meltwater per second. Source: National Snow and Ice Data Center.

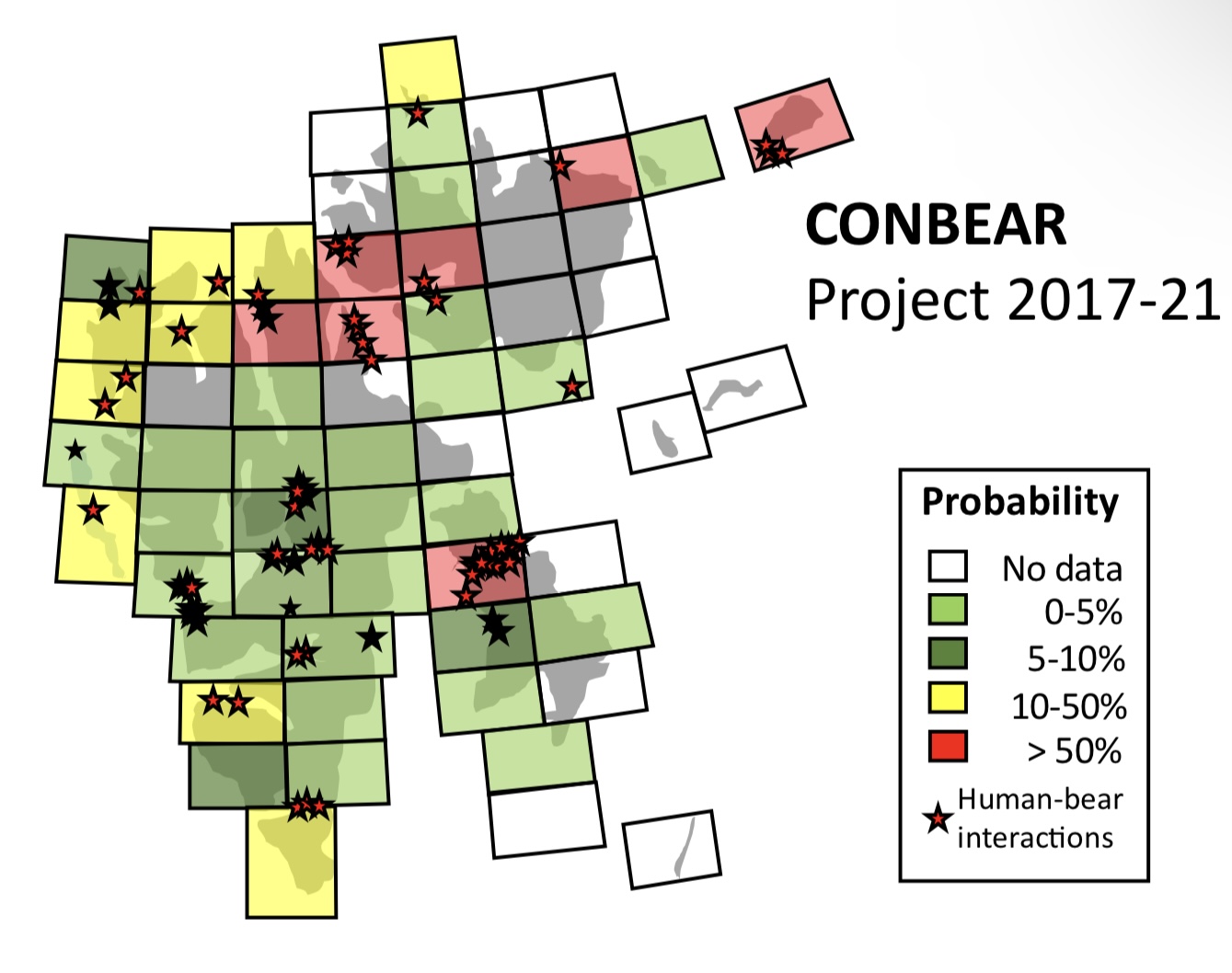

Image 2: When depicting the probability of encountering a polar bear and the human-polar bear interaction, it becomes clear that people consciously go to regions where polar bears prefer to stay. For example, in the southeast of the archipelago, many female polar bears have their dens in which they give birth to their young. Some tourist companies actually offer a polar bear guarantee. You can therefore imagine how often it happens that groups of tourists literally chase polar bears. Map: Bystrowska 2019.

Image 3: These are typical types of trash that, apart from most of the fishing nets not shown, are found during a beach clean-up in Svalbard. Picture: Vegard Holmelid.

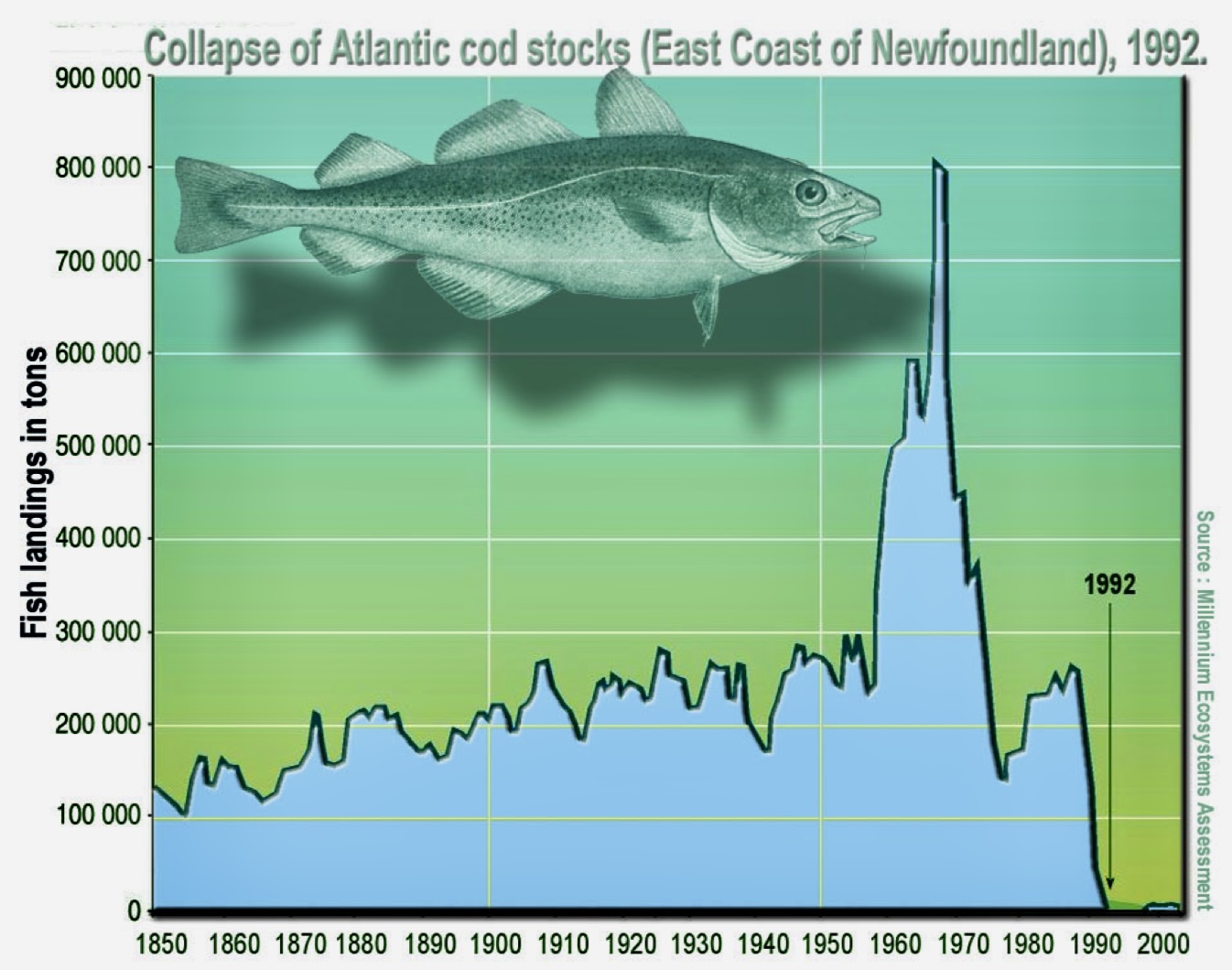

Image 4: Another problem that we have discussed at least briefly is overfishing. This map shows overfishing of Atlantic Cod in Newfoundland. But also in Svalbard, especially in the 1960s and 1980s, there were situations in which entire species were almost regionally wiped out. This has an immense impact on all higher trophic organisms in the marine food web. For the Barents Sea, there are strict quotas for individual commercially caught marine animals that Norway and Russia must adhere to. But there are often discrepancies and ambiguities. Source: Millennium Ecosystems Assessment.