Welcome back to Bio On The Rocks. The past days and weeks have been very eventful. Now that the sun is back, it not only lures students more into nature but also more and more tourists to the island. Some people had warned me about the darkness that awaited me when I arrived in Svalbard in early January. I always dismissed that quite quickly and countered with my attitude towards darkness and winters in Germany. The winters in Germany don’t bother me much, even though I would, of course, wish that climate change weren’t so noticeable and that we had an adequate amount of snow. The rainy days in the German winter don’t bother me. So, I also assumed I would cope with the darkness in Svalbard with the appropriate amount of vitamin D in tablet form.

Now, as is often the case with scientific questions with many influencing factors, I can’t really say what it was, but I definitely noticed a change in my mood for the past few weeks. Whether this is due to the fact that there is actually more sunlight, we do more activities, or I simply have settled in more, I cannot say. But I am very glad and grateful that the sun is back now and besides the great colours in the sky, some activities are possible again.

In line with the sun’s return in Svalbard, I attended an intensive course on “Stormy Sun and Northern Lights” at the Department for Space Physics in the last two weeks. I would like to delve into the fact that the sun is responsible for much more (in positive as well as rather negative terms for us) than we see at first glance.

When I arrived in Longyearbyen on 5 January, I was surprised by how dark it was during the day. Under such conditions, one would not immediately expect to still be influenced non-stop by the sun. Not in terms of brightness or warmth but because of the Northern Lights, both at night and during the day.

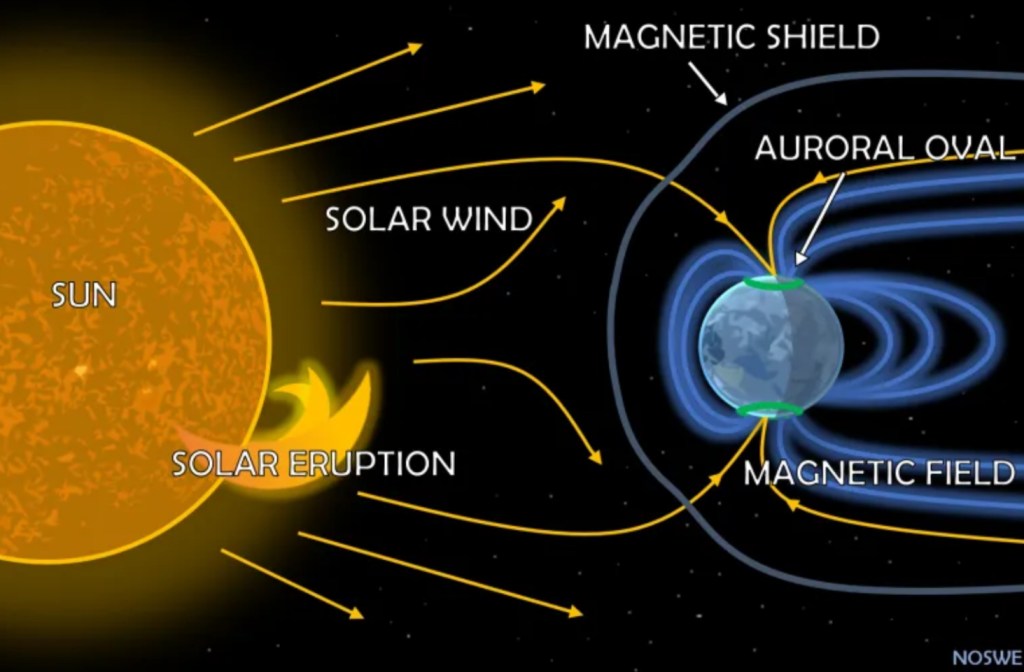

In brief, polar lights are formed when charged particles are ejected from the sun into space and encounter the Earth’s magnetic field. These particles are then directed towards the poles along the magnetic field lines, where they penetrate the atmosphere. There, they collide with gas molecules, resulting in a glow. The colours of the polar lights depend on the various gases with which the charged particles collide. Collision with nitrogen, the main component of our atmosphere, produces light in the purple wavelength spectrum. Collision with oxygen produces red light higher up in the atmosphere and green light lower down in the atmosphere.

What makes Svalbard special is that due to the archipelago’s position and the winter’s intense darkness, we can also see polar lights during the day. These are called “Daylight auroras” and occur when the magnetic field of solar winds and the Earth first encounter each other. There are other areas on the oval that circle the geomagnetic pole where Daylight auroras can be seen, but none of these areas offer adequate infrastructure for easy access.

If one thinks, “Wow, polar lights, I definitely want to see them…” one should not be disappointed if their own expectations are based only on postcard images, and they then see the significantly weaker polar lights with the naked eye. The eye, particularly the retina, is severely restricted in its colour perception in darkness due to its structure consisting of two different types of cells. Cones and rods can perceive colours and differences in brightness. When there is a lack of brightness stimuli for the rods, the eye is not good at distinguishing colours from each other using the cones. This explains why we see most things only in shades of grey at night. Another aspect is that with a camera, we can perform prolonged exposure photography and accumulate the incoming light from the polar lights, making them appear very bright in the pictures. And, of course, there are also Photoshop and similar programs available…

But I do not want to diminish the experience of seeing the Northern Lights for the first time in real conditions. Instead, I want to focus on how fascinating it is that these extraordinary celestial phenomena arise due to particles travelling from the sun towards the Earth. So, through space, a space that has long been considered an absolute vacuum and definitely is not one. It becomes even more impressive when you consider that these particles and energy originate in the sun’s core and take up to 200,000 years to reach the surface from the core. This is due to the extremely high density and the chain reactions present in the core.

Arriving at the surface, the sun’s special magnetic field is crucial. Like the Earth, the sun has a magnetic field, but it rotates at different speeds at the equator and the poles, as well as on the surface and in-depth. This creates high tensions, and the magnetic field exists in strong vortices that can build arcs. If these arcs are stretched too tightly, they can tear like a rubber band, sending extreme amounts of particles at incredible speeds of 1.5 – 3 million km/h towards Earth. Crazy, isn’t it?

It gets even crazier when you consider that this phenomenon also exists on other planets of the solar system. Specifically on the gas giants: Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune. The Aurora is formed in the same way and can exist because the planets have a magnetic field and an atmosphere. The atmosphere is partly composed of different gases than on Earth, which means that different elements interact with the particles from the sun and can produce different colours in auroras.

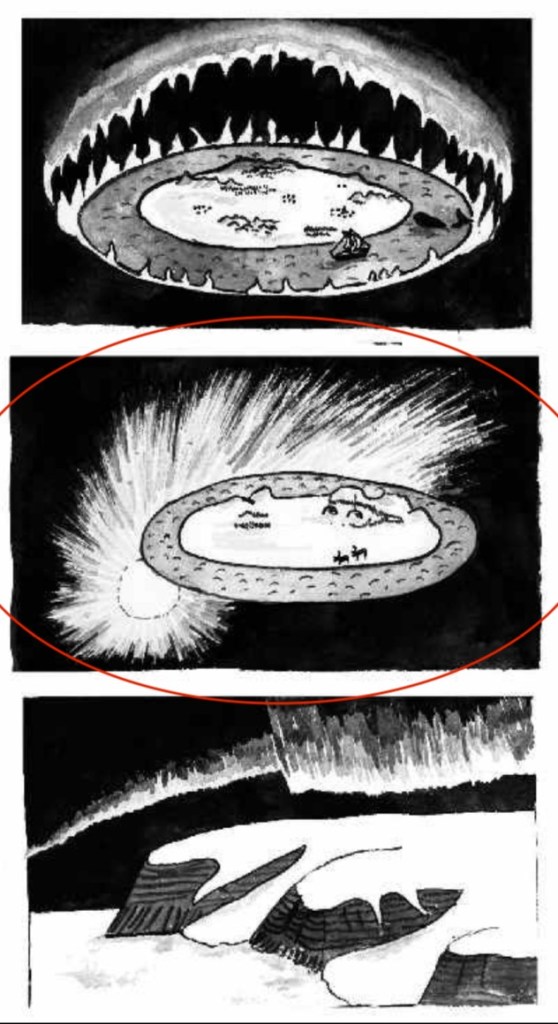

Like everything fascinating and initially inexplicable, people were initially afraid of the Northern Lights. In the past, they were seen as a bad omen; children were brought indoors; it was seen as a sign that “the Creator might be upset.” In contrast, Eskimos believed they were the souls of the deceased, clothed in mystical light, enjoying when the sun was absent (a notion also touchingly depicted in the children’s film “Brother Bear”).

The first attempt at a natural explanation for the Northern Lights can be found in the Norwegian Chronicles of the King’s Mirror from 1230 AD. It was speculated that there could be fires around the flat Earth, perhaps reflecting sunlight from below the horizon or fires in Greenland.

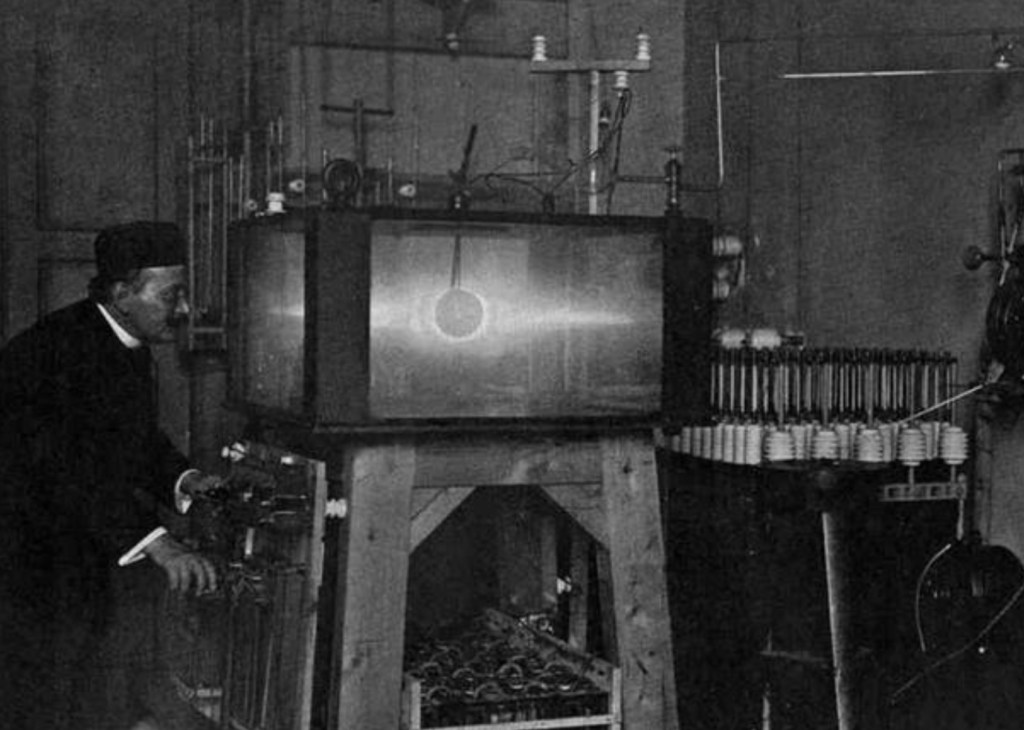

The Vikings gave the lights the name “Norðurljós” (Northern Lights), and Galileo Galilei was the first to use the name Aurora Borealis, which means “the dawn of the north.” It was then Kristian Birkeland, a Norwegian physicist, who made the crucial discovery and proved in 1896 that the sun continuously emits charged particles and photons, which are directed to the poles due to our Earth’s magnetic field. Birkeland was responsible for many more inventions and discoveries and was nominated an incredible seven times for the Nobel Prize in Physics. However, like most brilliant minds, his genius was recognised far too late, and he never received any of the Nobel Prizes. Because I find his life story so fascinating, I would like to delve deeper into it in another blog post.

However, the sun is responsible for much more than just the Northern Lights. Through so-called flares, proton storms, coronal mass ejections, and radio bursts (helpful for googling and research), sensitive and incredibly important systems for the safety of life on Earth can be endangered and damaged. Due to the extreme force of the electromagnetic waves and the highly energetic particles, both devices, like satellites in space and the Earth itself, can be affected. For example, GPS signals can be distorted, radio communication interrupted, and the electronics and orientation of satellites damaged. To predict such risky solar events and to study the chemical and physical changes of the sun, there are impressive research stations on Earth that communicate with countless satellites and observers in space.

We were fortunate to visit various research stations near Longyearbyen as part of the UNIS course, focusing on space weather. Among them, we also visited EISCAT (European Incoherent Scatter Scientific Association), a research facility in Norway, Sweden, and Finland, with its main location in Svalbard. There, they operate powerful radar systems to study the Earth’s atmosphere and ionosphere. By analysing radio waves, they gather information about the atmosphere, such as its composition and movement, as well as interactions with space. This research helps improve our understanding of “weather” and has implications for communication systems and space weather.

The massive equipment and the wealth of information about the Northern Lights during the course were fascinating. However, I believe that the fact we are continuously influenced by the activity and “whims” of the sun and the lack of secure predictions in many respects is much more impressive. Also, the extent to which humanity relies on technology that reacts so sensitively to changes in space weather was definitely not something I was aware of and has had a significant “aha”-effect on me.

Now, I hope for my further stay in Svalbard that the sun will be kind to us and send some pleasant solar winds and corresponding Northern Lights. Because from now on, things are happening quickly. On the 8th of March, the first official sunrise within Longyearbyen occurs, and then on the 20th of April, the polar day begins. Let’s see how my body will react to it. I think I can slowly but surely put away the vitamin D again. I’ll keep you updated on the changes in the sky over Svalbard. It will probably be as changeable as before. But let’s see, or feel, or find out… you know what I mean.