Welcome back. Today, we will delve into a topic that couldn’t be more fitting for Bio On The Rocks. Last week, I wrote a lot about the loss of sea ice and how humans can deal with the dangers that come with it.

Today, I want to dive deeper into the science and bring you closer to the basis of the marine food web. Due to the loss of sea ice, numerous changes have various impacts on the essential base of the food web. This involves the exposure of new habitats for non sea ice dependent organisms. However, this means the loss of sea ice itself as a unique habitat for highly specialised organisms. Another significant effect is the more intense and deeper penetration of light radiation into the sea, which can have special, yet poorly understood, consequences.

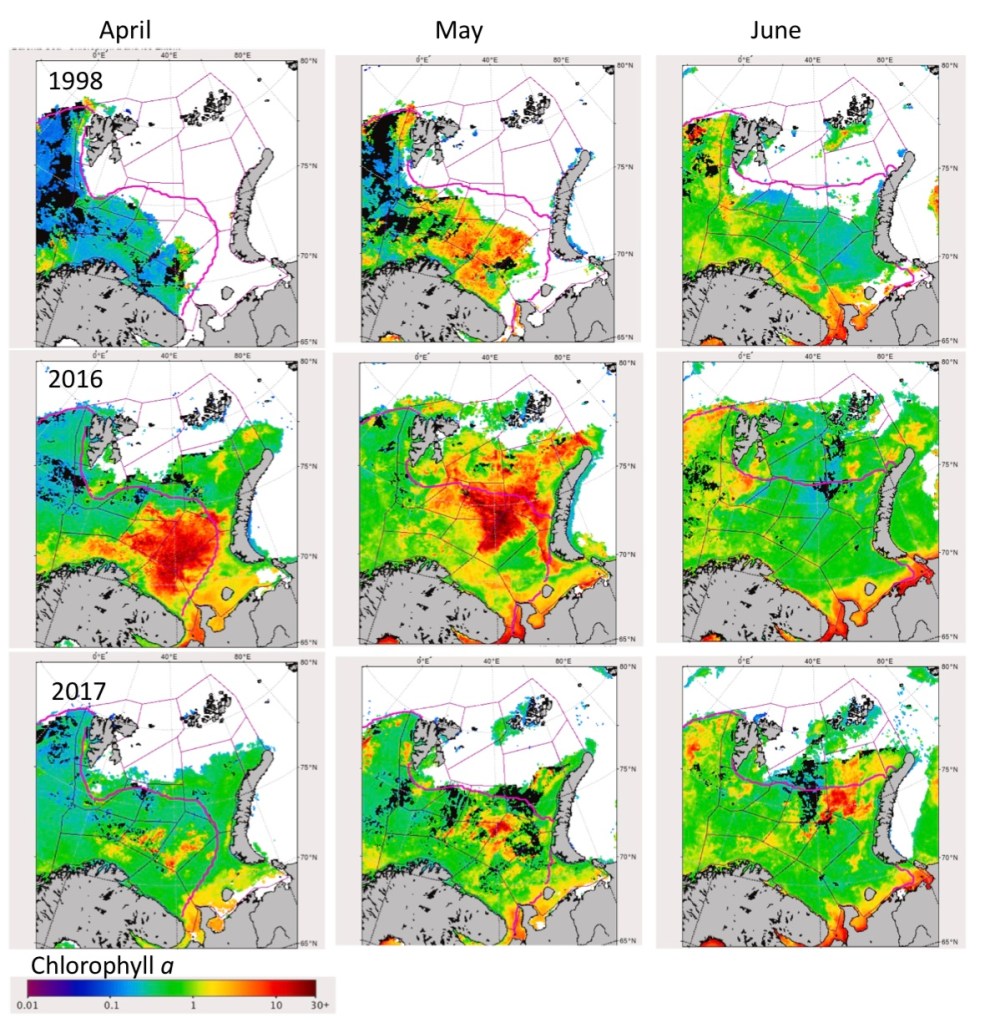

Let’s first look at phytoplankton. These organisms float in the water column, are not movable, at least horizontally and undergo photosynthesis. The study by Dalpadado et al. (2020) examined the dependency of phytoplankton growth and the resulting production of organic matter in relation to the extent of sea ice. As you can see from the maps, the high temperatures in 2016 and, consequently, the reduced extent of sea ice led to a particularly strong phytoplankton bloom (clearly visible in the high chlorophyll a levels, which are the photopigments in most phytoplankton species).

Therefore, one might initially assume that higher trophic levels benefit from increased food availability in the form of phytoplankton. Zooplankton is the next higher trophic level. They are also floating organisms (though some are significantly more mobile), and they gain their energy not through the conversion of light energy but through the intake of energy-rich substances. In other words, they consume phytoplankton and utilise the chemical compounds they produce.

However, it’s important to mention that many studies focus solely on the increase of chlorophyll and, thus, the enhanced photosynthesis rate in years with less sea ice spread. Yet, the composition of phytoplankton species plays a crucial role. It is evident that especially phytoplankton species, which benefit from climate changes, warmer waters, more intense light conditions, etc., are predominantly adapted to milder conditions. They increasingly migrate to northern regions, displacing Arctic species due to their competitive advantage.

On the one hand, the composition of phytoplankton species is relevant for nutrient supply to higher trophic organisms. On the other hand, it also affects the chemical conditions of the water column. Consequently, a change in species composition has relevance for the entire ecosystem. I will discuss further effects on zooplankton shortly. Now, let’s talk about another group of organisms that is incredibly important.

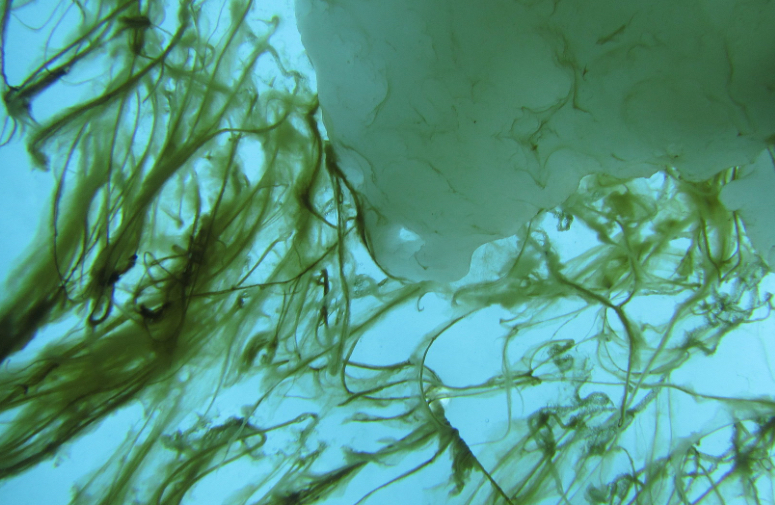

2. Pic: Intensive biomasses on the underside of multi-year ice. These often consist of the species Melosira arctica. Meereisportal.de (05.02.2024)

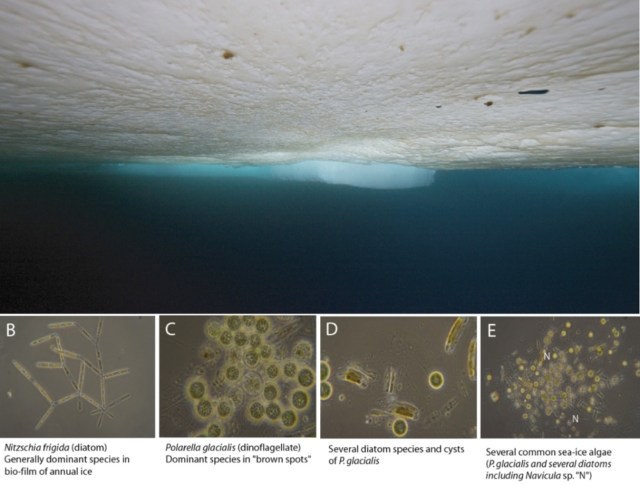

In addition to the organisms that float freely in the water column, the species that reside in or directly beneath the sea ice also play a particularly crucial role. The sea is a special medium that harbours areas with highly varying concentrations of salt and trapped gas bubbles. The brine channels provide habitats for various microorganisms, including the vital ice algae. Most of these species are endemic and highly adapted to life within the ice.

This means they are either adapted to low light conditions and can process it effectively. These are species that live under particularly thick, perennial ice layers, such as Melosira arctica. It could also mean they possess a high resistance to extreme light exposure. These species are found in the upper layers of ice or beneath very thin ice sheets. Due to this high level of adaptation, sea ice habitats significantly contribute to global biodiversity by supporting species that could not exist elsewhere on the planet. Typically, ice algae production is high in spring when ice conditions are most stable and sufficient polar daylight is already present. At that time, they become a particularly important food source for zooplankton species, especially because phytoplankton blooms may not yet have developed in spring when the ice remains thick.

A study by Weydmann et al. (2013) precisely examines this relationship. They draw comparisons between the more southerly, mostly ice-free Kongsfjord and the more northerly Rijpfjord, which is regularly covered with ice. In the studied year 2007, the Rijpfjord had an ice cover until June. This resulted in the phytoplankton bloom developing in the Rijpfjord about 2-3 months later due to lower light exposure than the Kongsfjord. However, it was observed that the zooplankton bloom did not show the same delay, only about one month. The most likely reason for this is the high biomass of ice algae, which spread from April to June on the ice in the Rijpfjord and provided the crucial food source for zooplankton. This ensured the early reproduction of Arctic grazers (zooplankton type).

Due to the loss of sea ice as a habitat for ice-associated organisms such as algae (but also bacteria, for example), not only do these organisms suffer, but also zooplankton and the entire biodiversity of the ecosystem are affected. Naturally, there are numerous higher trophic levels that, in turn, feed on the zooplankton and all intermediary levels.

One species at a higher trophic level that is struggling due to the loss of ice algae is the Arctic cod. Arctic cod are perfectly adapted to life under the ice in various ways. For example, the temperature for the most efficient food conversion and maximum survival rate is 0°C (Kunz et al. 2016). The larvae of this fish species feed on over 25% of ice algae cells directly (Gilber. The rest of their diet is determined by zooplankton, which, in turn, feed on ice algae. Arctic cod are key species within the Arctic marine ecosystem, playing a particularly vital role in maintaining stability and balance in this ecosystem. With the loss of ice algae, they are at risk, as are all species at higher trophic levels.

Another important aspect, particularly relevant but perhaps often overlooked because it occurs spatially separate from the sea ice, is the impact on benthic organisms (organisms living on the seabed). They, too, suffer from the loss of the rich carbon source provided by ice algae in the spring. Due to the regular thawing of the ice from below and the grazing by zooplankton, components of ice algae are released into the water column and transported over time to the seafloor. Without ice as a habitat for ice algae, this process of transporting energy-rich compounds (also known as the carbon pump) is disrupted.

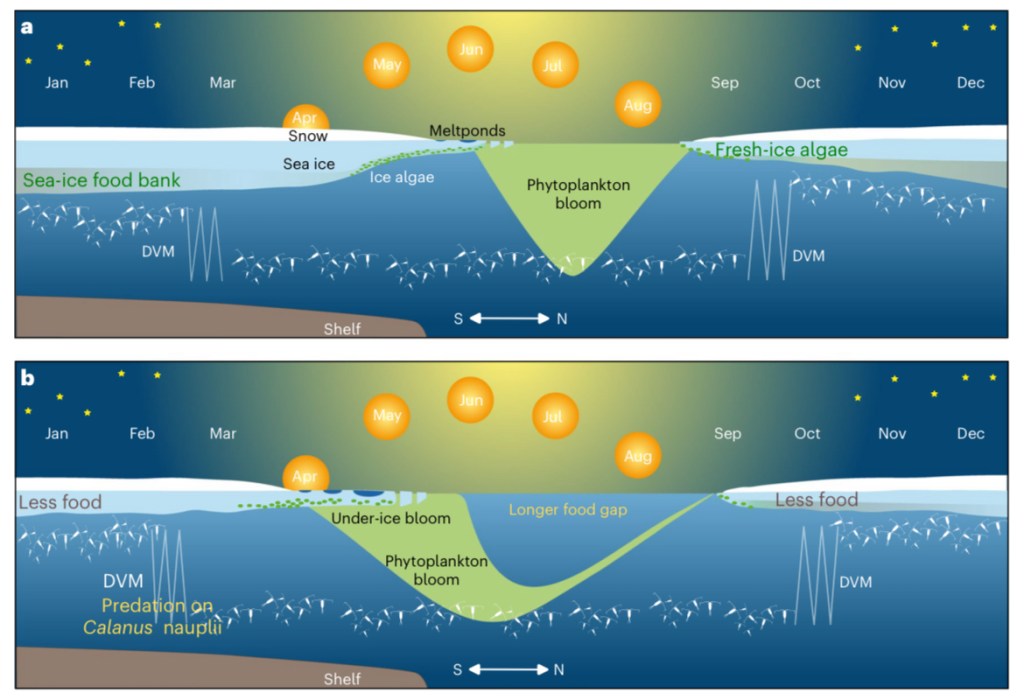

Finally, I would like to introduce you to a new study from the Alfred-Wegener-Institut (AWI). They have investigated a so far poorly researched aspect of sea ice loss. The shrinking and thinner sea ice cover allows sunlight to penetrate deeper into the water column, extending the period of sunlight in the water layers. As I have explained, this has an effect on primary production. However, the daily and seasonal changes in light intensity also affect zooplankton. The transition between day and night is responsible for the largest synchronous movement of organisms on the planet. Typically, zooplankton rises to the surface at night to feed on plankton and sinks to deeper depths during the day to escape predation.

In polar regions, zooplankton species also undergo a seasonal vertical migration. This means they predominantly stay near the sea ice during the polar night to feed on ice algae. In the spring, and with the increasing light intensity, they migrate to deeper water areas. However, there are also zooplankton species that build up reserves during the summer months and enter a kind of winter dormancy during the winter months. In both cases, the increasing light transmission through thinner sea ice impacts zooplankton’s daily and seasonal migration.

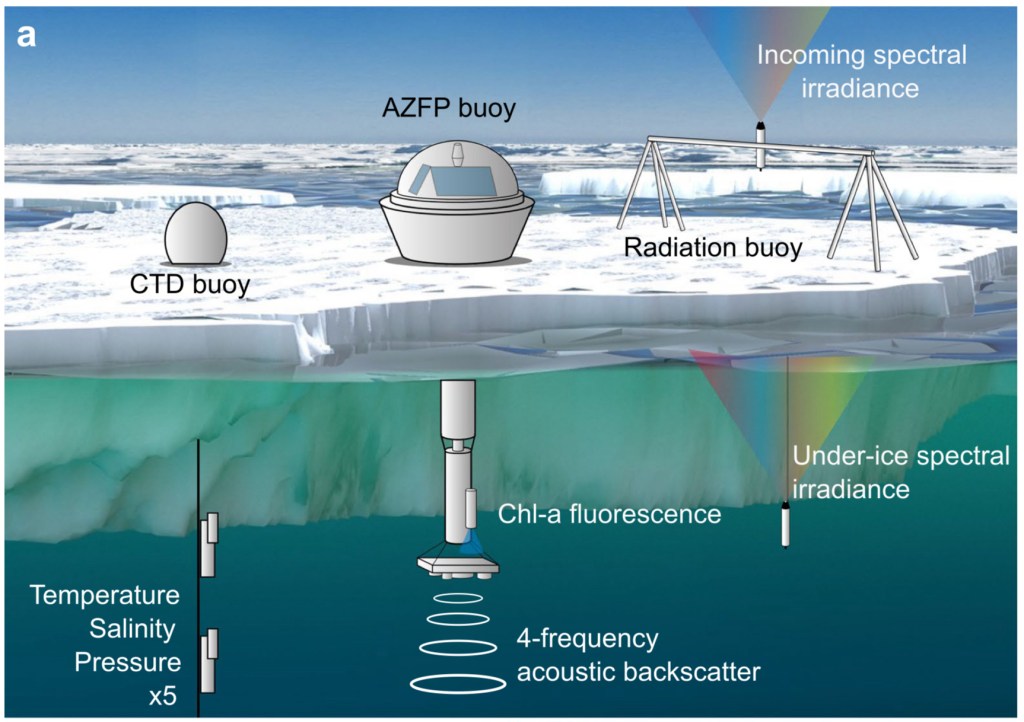

To investigate this in more detail, the AWI research group used an ice-anchored device called an “Autonomous Biophysical Observatory” in the Central Arctic Ocean. At the end of their Mosaic Expedition in September 2020, they deployed the device thousands of kilometres away from artificial light, noise sources, and human activity, where it remained until April 2021.

Through the collected data, they calculated the light intensity at which vertical migration was triggered. Based on other data already collected, they could also calculate how light intensity will increase beneath the ice in the coming years and estimate the effect this will have on the deep migration of zooplankton. The models predict that in approximately 30 years, the period during the year that zooplankton spends directly under the ice (near the food sources of phytoplankton and ice algae) will be reduced by up to one month. The longer period in the depth without adequate food will significantly impact the survival of zooplankton.

The loss of phytoplankton diversity, the sea ice as a habitat for organisms, and the changes in zooplankton distribution, population size, and diversity will have more profound effects on the entire ecosystem. But more on that soon. “Sea” You!

Dapaldado P., Arrigo K.R., van Dijken G.L., Skjodal H.R., Bagøjen E., Dolgov A.V., Prokopchuk I.P., Sperfeld E. Climate effects on temporal and spatial dynamics of phytoplankton and zooplankton in the Barents Sea. Progress in Oceanography. 185, 102320 – 102340 (2020).

Flores H., Veyssière G., Castellani G., Wilkinson J., Hoppmann M., Karcher M., Valvic L., Cornil A., Geoffroy M., Nicolaus M., Niehoff B., Priou P., Schmidt K., Stroeve J. Sea-ice decline could keep zooplankton deeper for longer. Nature climate change. 13, 1122 – 1130 (2013).

Gilbert M., LF L., Ponton D. Feeding ecology of marine fish larvae across the Great Whale River plume in seasonally ice-covered southeastern Hudson Bay. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 84, 19 – 30. (1992).

Kunz K., Frickenhaus S., Hardenberg S., Johansen T., Leo E., Pörtner HO., Schmidt M., Windisch H., Knust R., Mark F. New encounters in Arctic waters: A comparison of metabolism and performance of polar cod (Boreogadus saida) and Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) under ocean acidification and warming. Polar Biology. 39, 1137 – 1153 (2016).

Weydmann A., Søreide J.E., Kwaśniewski S., Leu E., Falk-Petersen S., Berge J. Ice-related seasonality in zooplankton community composition in a high Arctic fjord. Journal of Plankton Research. 35, 831 – 842 (2013).

Title Image: planktonforhealth.co.uk (05.02.2024)