While many of us associate the Arctic with the icy cold, the west coast of Svalbard hides a surprisingly “mild” climate. We owe this phenomenon to the unique ocean currents that bring warm water from the south. But the dynamics of this process and the interactions with the polar currents shape not only the climate but also the fascinating world of arctic oceanography.

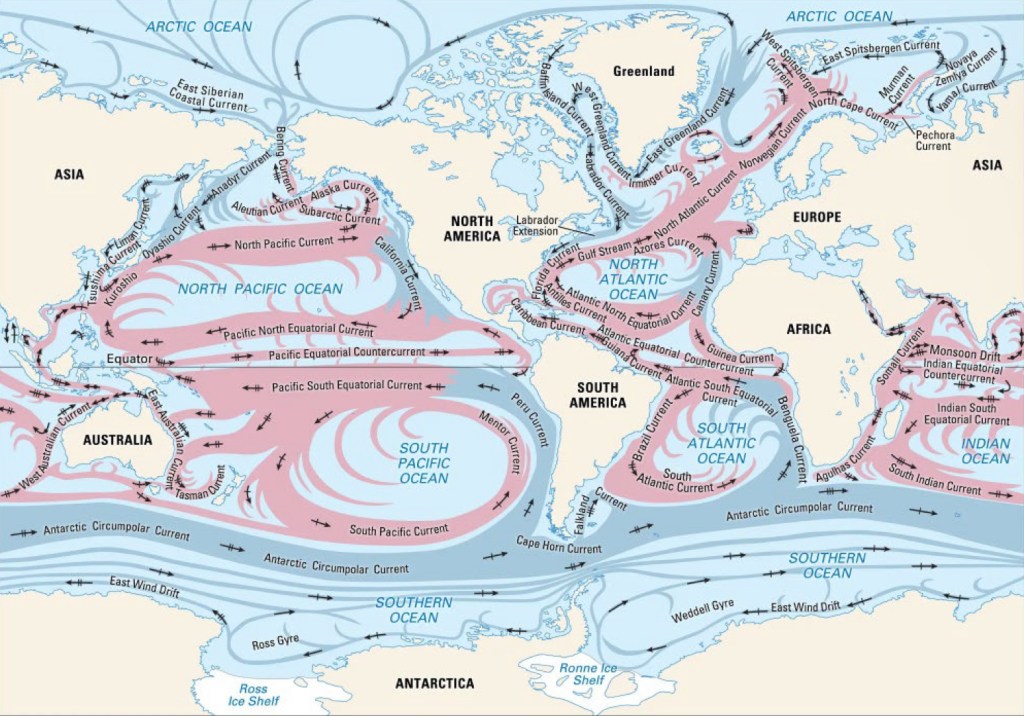

The physicochemical properties in the waters around Svalbard are constantly changing, influenced by temperature, salinity, oxygen levels, and other factors. These changes create gradients that cause water to move and are also driven by Earth’s rotation and the Coriolis force. The constant flow of water shapes the ocean currents, continuously supplying Svalbard with warm, nutrient-rich water.

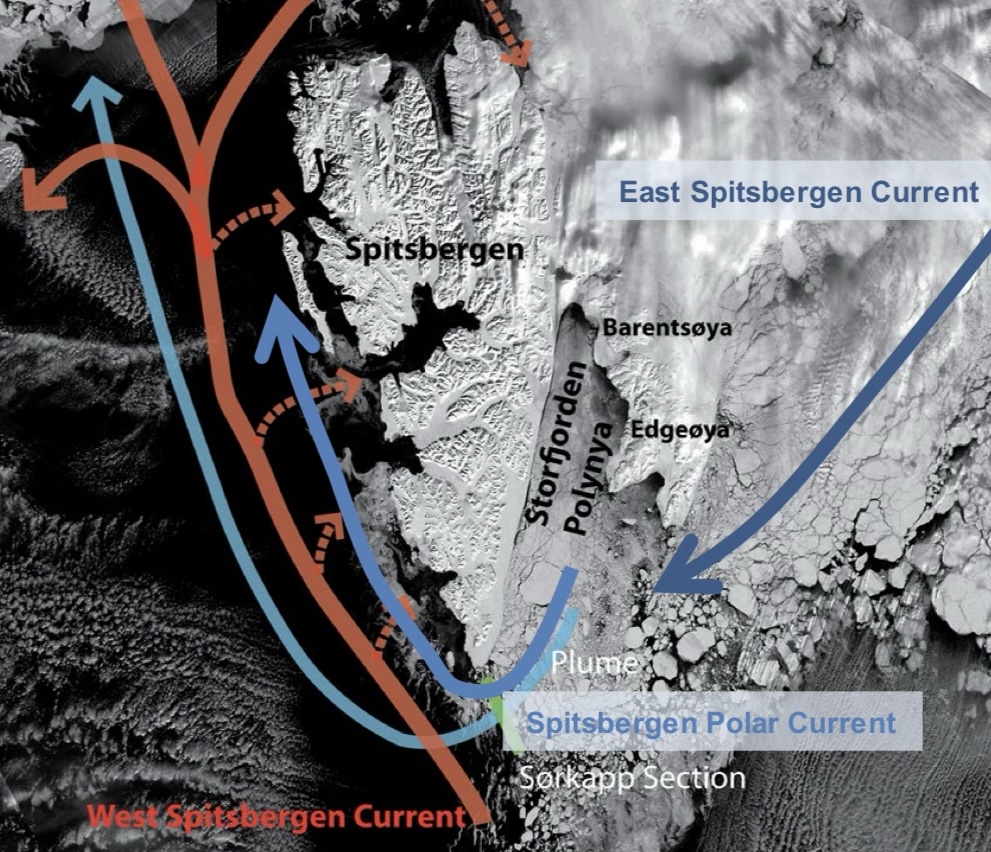

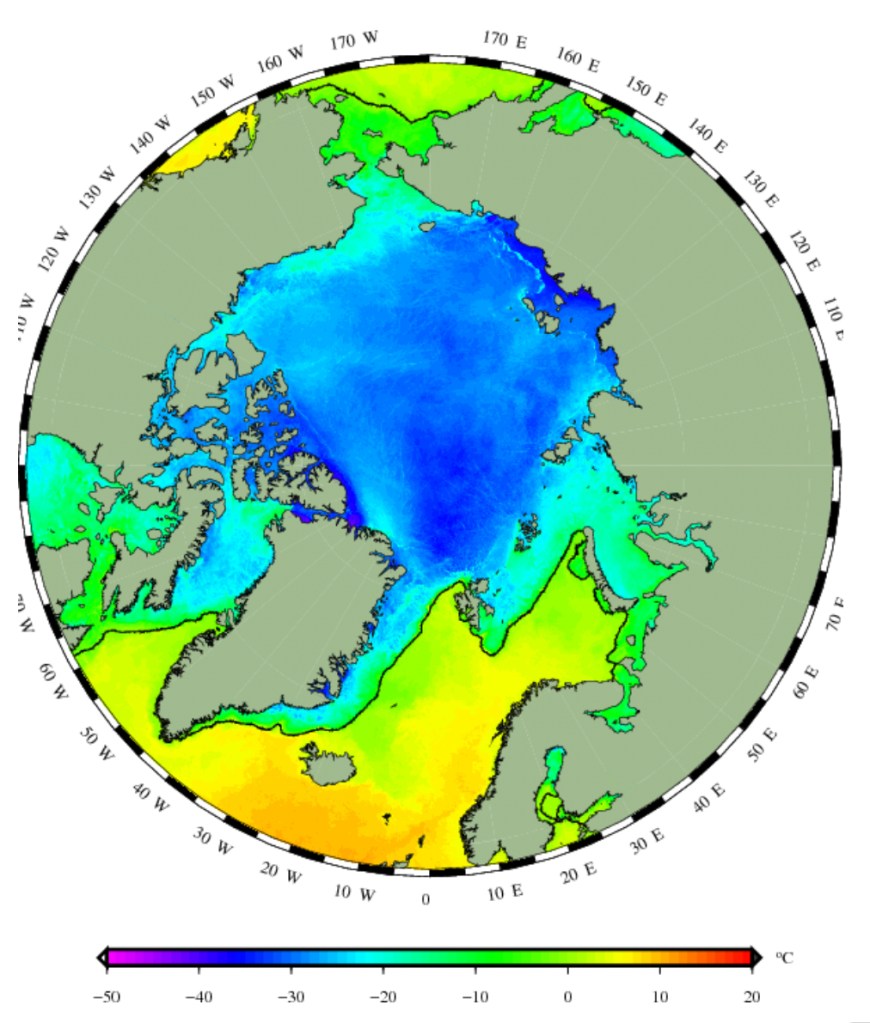

The west coast of Svalbard experiences a permanent flow of the North Atlantic and later the West Spitsbergen Current. The intensity and temperature of these currents vary seasonally, with the warm water intermittently rushing into the fjords like a pulse and briefly influencing the local weather. The narrow coastline of western Spitsbergen accelerates the water, increasing the current flow and transporting it to northern latitudes. These ocean currents mean that temperatures in Svalbard are actually 10-15°C warmer than average values at comparable latitudes.

However, there is still the Spitsbergen Polar Current along the west coast, which acts as a blockage and prevents too much warm water from flowing into the fjords. But this cooling effect is decreasing due to climate change, which means that the warm water can reach further and further into the fjords.

On the map, you can see in which special geographical area Svalbard is located. Even minor changes in current conditions or temperatures can have significant effects. Therefore, it is not uncommon to experience temperature fluctuations of up to 30 degrees Celsius in Svalbard within a few days.

But what distinguishes the fjords in Svalbard from those on the mainland in Norway when the temperatures in Svalbard are not so arctic? The crucial difference is that the temperatures, and especially the winds, are still cold enough! Cold enough to freeze the top layers of water and form an ice sheet.

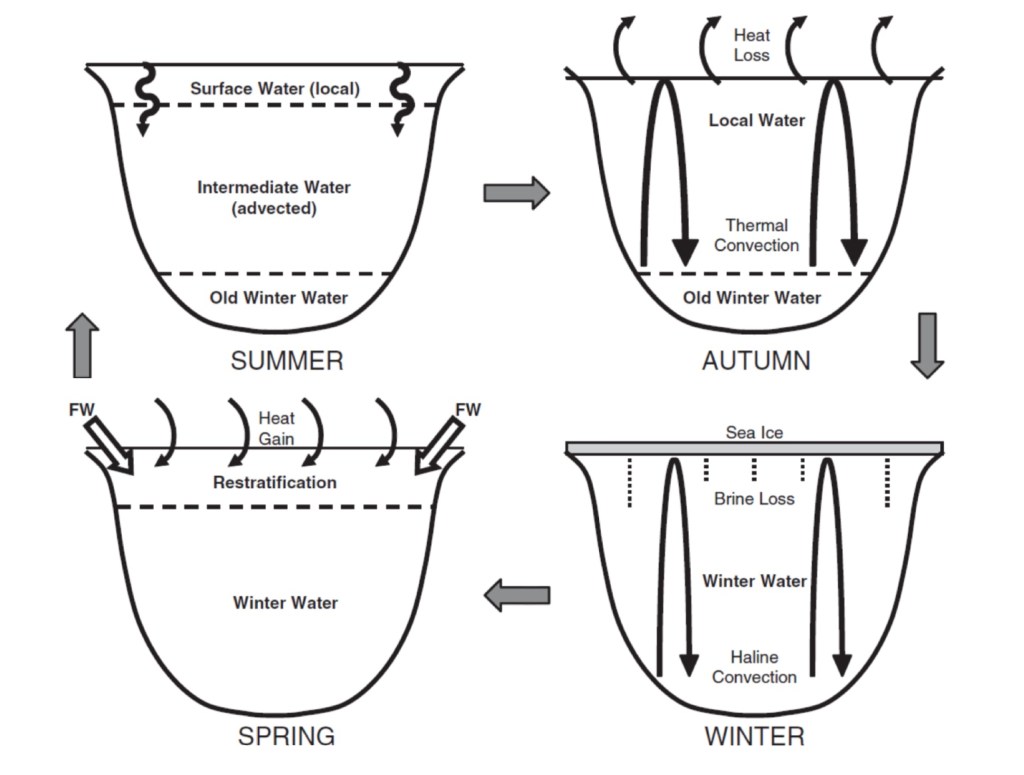

Let’s take a closer look at the different scenarios throughout the seasons. In summer, the uppermost part of the water column regularly receives fresh water from rivers and melting glaciers. This layer, therefore, contains comparatively little salt and heats up due to the intense sunlight. The water layer at the bottom is particularly cold and highly saline, which means it has a high density and remains at the bottom. In between, there is a mixed layer consisting of ocean currents and locally formed water. It is also relatively warm but contains more salt than the upper layers.

In autumn, the winds increase, solar radiation decreases daily, and the temperatures drop. The water flowing in with the stream is now colder and, due to its density, is now more separated from the local water formed on the surface.

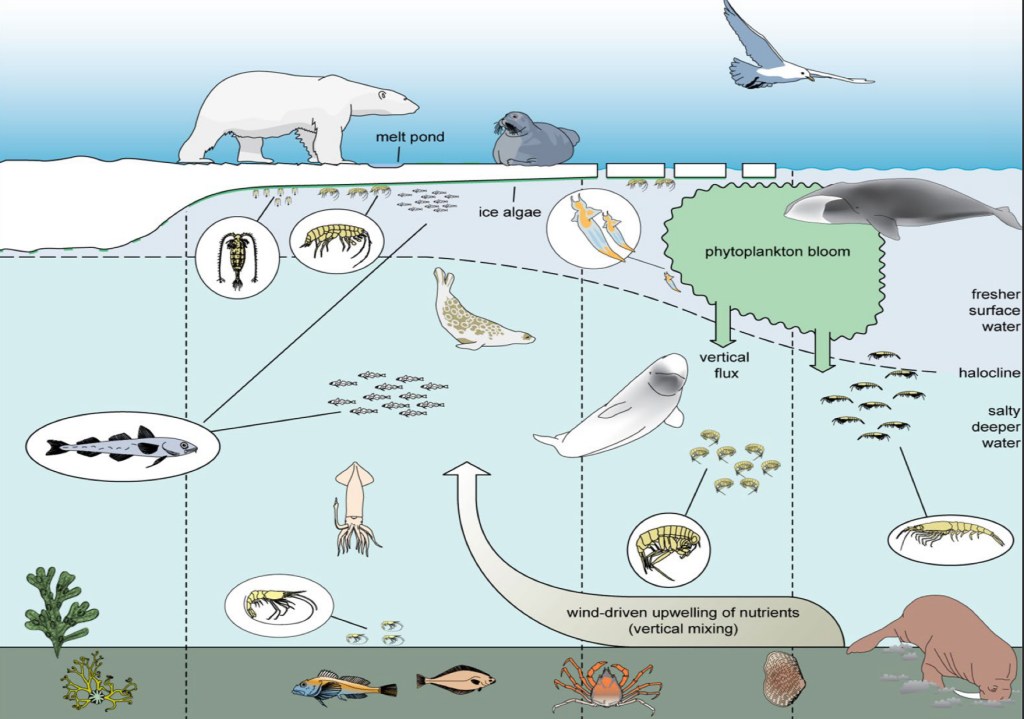

As soon as the water surface gets so cold in winter that freezing temperatures are reached, a layer of ice forms. The ice rejects the salt to the water below. This creates very cold and highly salty and therefore dense water directly under the ice layer, which sinks to the ground due to its gravity. This leads to vertical mixing, also known as haline convection. In spring, when the ice begins to thaw again, there is a sudden large influx of fresh water from above, and the three-layer can gradually rebuild.

It is also impressive that not only the weather and climate impact the fjords of Svalbard but also the topography. Even minor changes in the orientation of the fjord and blockages in the bottom sediment, so-called sills, which prevent the entry of warm water from the ocean currents, have an immense impact on the development of the water layers that can form in a fjord. It is possible that neighbouring fjords can provide completely different habitats for organisms. While a fjord can have a precise three-layering of water types in summer and therefore also provides the living conditions for organisms, a neighbouring fjord can have an ice cover in summer because the topography means significantly less warm stream water can flow in.

This diversity of habitats is crucial for marine fauna and flora and the entire marine ecosystem. Organisms that are specialized for the given conditions live in different areas. Stratification supports the emergence of complex food webs by allowing a variety of habitats within a limited space. The marine ecosystem, therefore, also offers a rich food source for many species that do not live permanently in or by the water. For seabirds, seals, polar bears, etc., what happens in the water column also plays a vital role. They depend on the ecosystem of the Arctic Ocean not to change too quickly so that they can continue to find suitable food in the years to come.

However, it is conceivable that a wide variety of climate change factors have an influence on these habitats of the ecosystem. For example, if it gets cold late in the year and there are periods of plus temperatures during the winter or the ice starts to melt more quickly in the spring, this will have an impact on the conditions in the sea and how the habitats are designed. This results in numerous effects on marine biology.

Because this topic is incredibly comprehensive, you should definitely take a closer look at some species in detail. I will publish more posts about it in March.